Part 1: Thomas Kentish of The Crosse

1. Early life

Thomas Kentish was born on 5 April 16311, the second son of William Kentish (1601-1642) of Burston Manor, St Stephen’s, St Albans and Rose Nichol or Nicholls2, who were married on 6 August 1628 in Chipping Barnet. William is usually referred to as a yeoman in documents from the period and records show that he and his family owned and farmed several farms in the St Albans area. William’s older brother, Thomas, owned Tenements Farm near Bedmond, close to St Albans, and this property passed down in that branch of the family for at least four generations, the description ‘of Tenements’ often being used after the name of the eldest son, to distinguish him from the many other members of his wider family called Thomas, including the founder of the charity.

William Kentish had acquired Burston Manor from the Bacon family when a young man and settled it on Rose at their marriage3. At this time, and until comparatively recently, the ownership of land was the route to status and power and, in Hertfordshire as elsewhere, there was a scramble for property in the aftermath of the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-41). Burston Manor had belonged to the Abbot of St Albans in the years leading up to 1540 and, along with all the Abbey lands, had been taken by the Crown and granted to Nicholas Bacon and Thomas Skipwith. The Kentish family were already well established in south Hertfordshire then. The sixteenth century marriage registers held by Hertfordshire Archives, which are incomplete, contain references to 21 marriages featuring members of the Kentish family in the St Albans and Watford area between 1543 and 1600, including that of Thomas’s paternal grandparents, Robert Kentish and Sibill Crosbey, who were married in St Michael’s Church, St Albans on 23 April 15994.

William and Rose had four surviving children: William junior, born in 1628, who inherited the Burston property, Thomas, born in 1631, Rose, born in 1634, and Robert, born in 1637. William senior appears to have prospered. In 1630, he and Rose acquired The Crosse (now usually known as Cross Farm) in the parish of Wheathampstead5 and, in 1633, he bought the adjoining farm at Ayres End6. On 24 July 1635, William senior granted the Wheathampstead lands to Thomas Nicholls, Henry Kentish and Ralph Kentish as trustees to hold for him during his lifetime and then for his younger son, Thomas7.

We do not know much about Thomas’s early life or education, but, since in his Will he asks to be buried ‘by my dear and loving mother’, we can assume that his upbringing was broadly a happy one. His Will also makes a number of bequests to members of his extended family and the impression we gain is of a large, inter-connected family which was advancing in the social scale. Thomas’s wall tablet in St Stephen’s Church, which was provided for in his Will, refers to him as ‘gent.’, suggesting that, in later life, he considered himself a gentleman, as evidenced by the coat of arms which is at the top of the wall tablet. Thomas’s success as a yeoman farmer and his adept property dealings are indications of a good education, possibly at St Albans Grammar School which, at this period, was located in the lady chapel of the former abbey church.

William Kentish senior died in 1642, at the early age of 41, and the Burston property passed to his eldest son, William junior, who later married Sarah Gee. As he was only 14 at the time of his father’s death, it is likely that his mother Rose managed the property at first, with assistance from the family. His brother, Thomas, succeeded to The Crosse in Wheathampstead as intended by the 1635 deed, although it is unlikely that he would have taken up residence there until some years later. A copy of a Court Roll entry in Hertfordshire Archives dated 2 June 1642 refers to the ‘presentment’ on the death of William Kentish of The Crosse and says that ‘Rose Kentish, widow of William, holds the property for life,’8 indicating that she held it as trustee for Thomas. A copy of a Court Roll entry in Hertfordshire Archives, dated 30 May 1667, refers to the admission of Thomas Kentish in reversion to The Crosse after the death of Rose Woolley, his mother9. She died in 1686, when she was 82, as shown on her gravestone next to Thomas’s in St Stephen’s Church, St Albans. According to the parish registers10, she was buried on 2 July 1686.

Later, both William junior and Thomas (and their younger brother, Robert) engaged in the enterprising management of land which was characteristic of their wider family. A conveyance in Hertfordshire Archives dated 5 July 1654 refers to a sale of land by William to ‘Thomas Kentish of Wheathampstead, yeoman.’11 As William was 26 and Thomas 23 at that time, we have a picture of two vigorous young yeomen farmers buying and selling property in order to consolidate and extend their estates. William junior, however, died in 1668, when he was only 40.

There is no record that Thomas married whilst a young man. A document dated 21 June 169512, which represents a marriage settlement, refers to the bargain and sale (conveyance) of a barn at Ayres End Green and other property from Thomas Kentish to William Knowlton of Park Street and Thomas Knowlton of Hemel Hempstead ‘to hold to the use of Thomas Kentish and Anne his intended wife, being daughter of Abigail Knowlton, widow, sister of the said William and Thomas Knowlton.’ The deed also refers to a payment to Abigail Knowlton of £200 and £100 in trust. Assuming that Thomas and Anne married in 1695, he was 64.

2. Property transactions

By the time he died in 1712 at the age of 81, Thomas was the owner of extensive property in Wheathampstead, Codicote, Welwyn, St Stephen’s (St Albans), and Bushey in Hertfordshire and at Campton in Bedfordshire. The Will includes detailed bequests relating to all of these.

It is not clear from extant records why Thomas engaged in a flurry of land acquisition in the 1690s, when he was in his 60s. It may have been that he was already intending to establish his younger relations as property owners or that he had simply become wealthy enough to do so, the purchase of land being the natural way to invest accumulated funds. As is evident from his later Will, where he refers to a new kitchen, he also improved and modernised his house round about this time. When his mother had died in 1686, she had left the bulk of her belongings, after a number of smaller bequests, to her ‘good sonne,’ Thomas Kentish, and made him her executor13. As already noted, he married Anne in around 1695 but, before that, he had entered into a mortgage by demise of a property in Frogmore, with land in Bushey (‘messuage, tan yards etc. at Frogmore near the water corn mills, three corner field, chalk-dell fields, Bushey’) from John Finch14. A mortgage by demise was a mortgage whereby the mortgagee became the landlord. The payment by Thomas was £350 and there was to be a peppercorn paid yearly (if demanded) by John Finch on the feast of St Michael the Archangel. The impression we gain from this is that, whereas John Finch was in need of capital, Thomas Kentish had money to spare.

On 18 January 1698/915, he entered into a ‘Release (following lease for a year)’ from John Poyner, gentleman, and Sir William Lytton of Knebworth, knight to Thomas Kentish of The Crosse, gentleman, of the manor of Scissivernes in Codicote and other land in Codicote and Welwyn16. The payment by Thomas was £1856 and 5 shillings, out of which £443 and 15 shillings was payable to Sir William Lytton. After Thomas’s death, this property passed to his principal heir, Thomas, the son of his younger brother, Robert, and the manor remained with this family until the middle of the nineteenth century, when the Revd John Kentish died without issue in 185317.

3. The farm at Campton (Camptonbury or the Burystead)

The early title deeds for Camptonbury Farm are at Bedfordshire and Luton Archives, along with other records relating to Kentish’s Educational Foundation. Thomas acquired this property in 1698. On 7 June 1697, he entered into an Agreement to purchase the property for £202418, a substantial sum. In October 169719, Thomas entered into a Conveyance (Lease and Release) with John Ventris and William Gibbons and, in May 1698, there was a Bargain and Sale from John Ventris and William Gibbons to Thomas Kentish20. The Conveyance provides details of the land that was included, much of which is recognisable today, although some was in the open fields which were later the subject of the Meppershall Enclosure Award of 185321. The farm was tenanted. John Ventris, who was a Justice of the Peace, was the son of Charles Ventris, who had fought in the Civil War on the King’s side and been knighted in 164522. The Ventris family lived at Campton Manor House. Throughout the latter part of the seventeenth century, Camptonbury (the Burysted or Berrysted) had been the subject of a number of mortgages and remortgages and it may be that John Ventris had needed to raise funds at various times, especially as Campton manor had been sequestrated during the Commonwealth, following his father’s death. John died in 1706.

When Thomas wrote his Last Will and Testament in 1711, he decided, not only to charge Camptonbury with an annual sum out of the rents (known as a rentcharge) for the poor of Campton, but to leave the property in trust for the benefit of poor boys from his extended family. We can only speculate about his reasons for his choice of Camptonbury for this purpose. It was the only property which he owned in Bedfordshire and it was the furthest from his own home in Wheathampstead, so perhaps he felt that it was distinct from his other property. In any case, it was a generous charitable bequest.

The farm, which consisted largely of arable land and pasture, was tenanted by the Lincoln family for most of the eighteenth century23. Finally, in 1805, William Lincoln’s nephew allowed his uncle’s executor, William Squire of Shefford, miller, to take over the lease and William Squire was permitted by the trustees to assign the lease to William Lamb24. The farm has remained in the occupation of the Lamb family ever since, a remarkable example of continuity. In 1828, the farm was surveyed by Mr J H Rumball, surveyor, of St Albans. He found ‘the buildings are out of repair, the farm has been well farmed, the arable allotments were formerly small properties, but they are fast improving’25.

We do not know what the original farmhouse looked like, as it was demolished in around 1851 when the present house was built, but it may have resembled the old, timber-framed farmhouses which can still be seen in the locality. The old barns, which still survive (although converted into dwellings) were thatched until the middle of the twentieth century.

In 1848, an excavation of a supposed Roman barrow was carried out on the farm by Mr Inskipp of Shefford. This revealed human remains, iron and bronze spurs, a knife and a possibly Samian Ware bowl26. The name ‘Burysted’ probably derives from the Old English for ‘fortified place’. The excavation site appears to be close to Gravenhurst Road and is catalogued by English Heritage as Monument 362513. The finds are in the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology but not on display.

4. Thomas Kentish’s Will of 1711

Thomas Kentish’s Will is dated 15 September 1711. He died on 22 August 1712 and probate was granted on 22 September 1712. The executors were Godman Jenkyns, his nephew, and John Nicholls of Idlestrey, probably a relation on his mother’s side. Idlestry is an old name for Elstree. There is a record in Hertfordshire Archives of the marriage of John Nichols (or Nicholls) of Elstree and Mary Jenkyns of Harpenden on 29 April 1701. It seems very likely that this Mary was the daughter of Godman Jenkyns and his wife, Sarah, in which case Thomas’s executors were his nephew and his nephew’s son-in-law. In the Kentish ‘clan’ generally, there was a great deal of inter-marrying.

Thomas’s Will is several pages long and very detailed, providing us with more information about Thomas’s household and property than any other single source. There is no apparent record of a separate inventory. The Will begins with a traditional Christian statement about death and a commendation of the testator’s soul to Almighty God my Creator steadfastly believing through his Holy Spirit by the bitter Death and bloody passion of his only Son and my ever dear and blessed Saviour Jesus Christ.27 Thomas then asks for his body to be buried in a decent and Christian manner and later says that he wishes to be buried by my dear and loving Mother Rose Woolley.

After the preamble, the Will makes a number of charitable bequests, beginning with five pounds to the poor of Wheathampstead28, where I now dwell, forty shillings to the poor of Harpenden, twenty shillings to the poor of Welwyn29, twenty shillings to the poor of Codicote30, forty shillings to the poor of the parish of St Stephen, where I was born, and twenty shillings to the poor of Campton in Bedfordshire. The executors were charged with distributing these funds.

The Will goes on to set up annuities, payable out of rentcharges on his property in the parishes concerned, for the poor of Wheathampstead (ten shillings), Welwyn (ten shillings), Codicote (ten shillings). St Stephen’s (ten shillings)31 and Campton (ten shillings). These funds were to be paid to the respective churchwardens and overseers of the poor, to be spent on bread and distributed each year on Thomas’s birthday, 5 April.

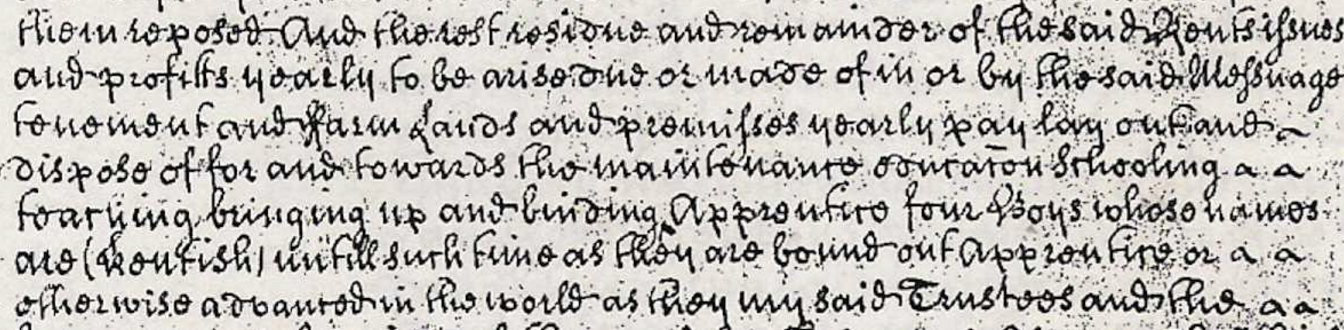

The next section of the Will deals with the establishment of what later became Kentish’s Educational Foundation. He leaves to Godman Jenkyns Esq, Robert Jenkyns Gent., John Nichols of Idlestrey (ie Elstree), William Knowlton and Thomas Kentish the Younger of Tenements, their heirs and assigns my Messuage, Tenement and Farm situate and being in Campton aforesaid and Meppershall or in one of them in the County of Bedford…which I lately purchased of Major Ventrice and all other of my lands and Tenements in the said County of Bedford …upon special trust and confidence. Thomas provides for a sum of ten pounds, annually taken from the rents, to be paid to the trustees for their care, pains and charges. The residue of the rents and profits is to be applied to the maintenance, education, schooling, teaching, bringing up and binding out apprentice four boys whose names are Kentish. If, at any time, four boys of the name of Kentish cannot be found, as many others of my near relations as shall make up the number of four boys for the time aforesaid are to be substituted. The Will next provides for the trustees and their survivors to appoint six or more new trustees in order to maintain the succession, the new trustees always to be named and appointed by the surviving trustees.

After making the charitable bequests, the Will proceeds to make bequests to Thomas’s immediate and extended family. By the time Thomas wrote his 1711 Will, his property was extensive, as we have seen. The Will tells us that his property at the Crosse amounted to around 160 acres and consisted of arable lands, meadow and pasture and wood grounds (much still identifiable today). Although a farm of 160 acres would be seen as fairly small today, it would have been regarded as a reasonable size in 1711. Thomas also owned Ayres End Farm, Camptonbury Farm, Sissavernes Manor or Farm in Codicote and Welwyn, a farm in St Stephen’s parish (let to James Freeman) plus some woodland (not let), and copyhold property in Bushey lately purchased of Francis Ligo. Thomas provides for his female relations by granting annuities derived from rentcharges on his farms and his male relations by bequests of property. This would have been normal for the period.

The bequests are (in the order given in the Will):

Annuities

His wife Anne, for her whole life, if she continued a widow – an annuity of £20 paid from the rent from the Crosse.

Elizabeth Knowlton, widow, one of the daughters of his sister Rose and Robert Jenkyns deceased – an annuity of ten pounds, from the Codicote/Welwyn property.

Rose Hull, sister of Elizabeth Knowlton – an annuity of ten pounds from the Codicote/Welwyn property.

Nehemiah Knowlton, son of Elizabeth Knowlton – an annuity of ten pounds towards his bringing up, until he was sixteen. This was also from the Codicote/Welwyn property. The annuities to Elizabeth, Rose and Nehemiah were to be paid in equal instalments on the usual feasts of the Annunciation of the Blessed Lady Saint Mary the Virgin, St John the Baptist, St Michael the Archangel and the birth of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.

Bequests of property

Thomas Kentish, son of his late brother, Robert – the Crosse, Ayres End Farm, all the property in Codicote and Welwyn lately purchased of John Poyner, and all the property in St Stephen’s parish. The Will appoints Michael Nicholls of Aldenham and Joseph Carter of St Michael’s to act as trustees for his nephew Thomas. The Will also establishes the succession of ownership, allowing for lack of further sons, namely, any sons of Thomas Kentish up to the number of ten, the eldest surviving son becoming the heir. If this line failed altogether, then the Crosse, Ayres End Farm and the St Stephen’s property were to go to Thomas Kentish, the son of Robert Kentish of Waterdell32, and his heirs. The Codicote and Welwyn property would similarly go to Robert Kentish, another son of Robert Kentish of Waterdell, and his heirs. In both these cases, Michael Nicholls and Joseph Carter were to be trustees.

William Kentish Nicholls, son of Thomas Nichols, late of Bushy Gent., – copyhold property in Bushey, lately purchased of Francis Ligo. This property was to pass, after William’s death, to his brother, James; after James’s death to his brother Joseph; after Joseph’s death to his brother Michael; after Michael’s death to his brother Godman; and after Godman’s death to his brother Samuel. After Samuel’s death, the property was to go to Robert Kentish, son of Robert Kentish of Waterdell, and his heirs for ever.

Personal bequests

Rose Hull, daughter of Rose Hull mentioned above – £100.

Rose Knowlton, daughter of Elizabeth Knowlton – £100.

Other grandchildren of Thomas’s sister, Rose – £50 each.

Children of Thomas Nicholls deceased and Mary his wife33 (but not William Kentish Nicholls) – £50 each.

Thomas Kentish, son of Robert Kentish of Waterdell, – £100.

[Legacies to young people to be paid when they were 21.]

Anne, his wife; Godman and Sarah Jenkyns; Mary, the wife of Thomas Nicholls deceased; Robert and Sarah Jenkyns; John and Mary Nicholls; Elizabeth, widow of Nehemiah Knowlton deceased; Daniel and Rose Hull; Thomas Childston – £10 each to buy mourning clothes and rings to wear at his funeral.

Thomas Knowlton and his wife; William Knowlton; and Thomas Kentish his nephew – £5 to buy mourning clothes.

Anne, his wife – £100 and all the goods and chattels I had with her at the time of my marriage together with all the furniture in the chamber over the new kitchen in my now Dwelling House and in the Garret over the kitchen; also, six pairs of flaxen sheets, several other items of linen and the little nag that she rode.

Anne, his wife, Sarah, wife of Godman Jenkyns, Mary the relict of Thomas Nicholls of Bushey, Rose the wife of Daniel Hull and Elizabeth the relict of Nehemiah Knowlton – all the rest of the Diapery, Linen and Household Goods unbequeathed.

Thomas Kentish (his nephew) – all the rest of his goods, chattels, bonds, mortgage securities and personal estate unbequeathed, after all debts and expenses were paid, These were to be his when he reached the age of 21 (he was born in 1697). If he died before then, these assets were to go to the grandchildren of Thomas’s sister, Rose, and to the children of Thomas Nicholls of Bushey and Mary his wife, to be divided amongst them equally.

Thomas’s servants – ten pounds each.

Nehemiah Knowlton – £40 for him to be apprenticed.

Instructions to executors

Thomas asks his executors to spend two hundred pounds on his funeral and to lay a very good stone over the grave of his brother, Robert, and one over his own grave. He also asks for a tombstone to be set up near his grave on the wall of the church with such inscription as he will direct or as they see fit. Finally, he directs that his executors should be repaid any reasonable expenses.

At the end of the Will, Thomas revokes all former Wills and says that he has signed all six sheets and a part of a sheet that the Will has been written on.

Part 2: The charity gets going

1. The eighteenth century: apprenticeships and trustees

The first century of Thomas Kentish’s charity is possibly better documented than the next century. Although early Minute books do not apparently survive, the documents held by Bedfordshire and Luton Archives include leases of Camptonbury Farm, a number of apprenticeship indentures dating from the eighteenth century, and deeds of appointment of new trustees. It seems from these that the trustees took their duties seriously after the establishment of the endowment in 1712, letting out the farm and providing funds for education, maintenance and apprenticeships.

The system of apprenticing boys, and, to a lesser extent, girls, to crafts and trades dates from the Middle Ages. The basic system was for the parents or sponsors to pay a premium to the master/mistress of a trade in exchange for their son or daughter being taught the trade and lodged and fed for a period of, typically, seven years. The amounts could be quite large, certainly comparable to university tuition fees today.

The system was regulated by law. An apprenticeship indenture34 was a legal document whereby a master, in exchange for a sum of money (the ‘premium’), agreed to instruct the apprentice in his or her trade or ‘mystery’ for a set term of years. The provision of food, clothing and lodging was generally part of the agreement. Readers of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations will remember how Pip was apprenticed to his brother-in-law, Joe Gargery, as a blacksmith. It was not at all uncommon for apprenticeships to be provided within a family circle in this way. An apprenticeship could provide the route to a prosperous career.

An Act of Parliament in Queen Anne’s reign (8 Anne, cap. 5) ruled that from 1 May 1710 a tax was to be paid on all apprenticeship indentures excepting those where the fee was less than one shilling or those arranged by parish or public charities. Trades which had not existed in 1563 when the Statute of Apprentices became law were also not liable to the tax. The most notable example of this was the cotton industry. A later Act (9 Anne, cap. 21) made the tax permanent, but it was abolished in 1804. The last tardy payments continued to trickle in until January 1811. Many apprenticeships did not last the full term because of the death or bankruptcy of the Master, or because the apprentice ran away.

The trustees of Thomas Kentish’s charity would have needed to consider how much money they had in order to fulfil the terms of the trust. The rent from the farm was around £80.00 per year for the whole of the eighteenth century, going up to £142.00 per year in 1810 but subsequently going down again. Out of this, they would have paid themselves £10.00 for their trouble and they would also have paid out the rentcharge of ten shillings to the poor of Campton35. They would have needed to keep funds in hand for the landlord’s obligations to the farm. After these payments, they were obliged to assist four poor boys with the name of Kentish. The Will enabled them to pay for maintenance, schooling and other needs of the beneficiaries, as well as the binding out apprentice. We do not have many records from this period which show how the trustees spent the funds, but there are still some apprenticeship records held with the Foundation’s papers at Bedford. These cover the period 1742 to 1761 and provide a fascinating window into the work of the trustees at that time and into social conditions generally.

Most of the indentures concern boys living fairly locally. For example, on 29 May 1742, Thomas, son of Daniel Kentish of St Michael’s, St Albans was apprenticed to Samuel Pope of Abbots Langley, carpenter, for the sum of £10.0036. Other boys went further afield, often to London. On 20 February 1748/9 [date old-style], Thomas, son of Richard Kentish of Rickmansworth, labourer, was apprenticed to Richard Thomas of St Clement Danes, cooper, for a premium of £12.0037.

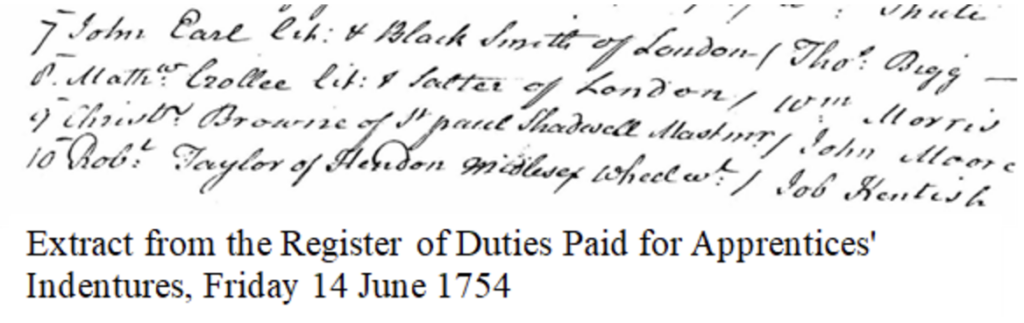

During this period, two brothers were apprenticed to the same Master. On 23 April 1754, Job, son of Job deceased and Martha of St Stephen’s, St Albans, husbandman, was apprenticed to Robert Taylor of Hendon, wheelwright for £10.0038. Six years later, on 11 August 1760, his brother Robert joined him. The premium had risen to £15.0039. No doubt their widowed mother, Martha, was pleased to have her lads living and working together with what one hopes was a good Master.

One family of Kentishes lived in New Malton, Yorkshire in fairly comfortable circumstances. We find that, on 1 July 1745, Richard, son of William Kentish of New Malton, cheesemonger, was apprenticed to Lancelot Fairfax of New Malton, apothecary. This was a little further up the social scale than wheelwrights and coopers and the premium of £20.00 reflected that40. Fifteen years later, on 1 August 1761, Nathaniel, William Kentish’s godson, was apprenticed to Richard Kentish of Bridlington, surgeon and apothecary, for the even higher sum of £25.0041. By this time, William Kentish himself was a ‘butter searcher’ – a sort of quality control inspector acting for his guild or association.

There are deeds of appointment dating from the eighteenth century which show that the trustees conscientiously appointed new trustees when these became necessary. On 6 October 1739, for example, the then surviving trustees, Godman Jenkyn, Robert Jenkyn and Thomas Kentish of Tenements, appointed Thomas Kentish of St Albans, William Nicoll, the Revd John Cole, Samuel Clover, John Pope and Henry Smith to join the trustee body, making nine trustees in all42. There were further deeds of appointment in 1748, 1768, 1785 and 1831, although, as we shall see later, the number was not always nine. Members of Thomas Kentish’s immediate and wider family formed the majority of these trustees but other suitably worthy individuals were recruited. Many of the trustees are described as ‘gentlemen’ in the deeds of appointment but we also find woolstaplers, grocers, yeomen, a draper and the grand-sounding ‘Joshua Iremonger Kentish of Westminster, gentleman’43.

2. The nineteenth century: a few irregularities

In the early years of the nineteenth century, the trustees found themselves with a problem. By 1830, most of the trustees appointed in 1785 had died, leaving the Revd John Kentish, by then a dissenting minister working in Birmingham, and Ralph Thrale Smith, who had become mentally incapable. We do not know the exact cause of Mr Smith’s disability, but, as he must have been very elderly by then, this may have been a form of dementia. The appointment of new trustees was an urgent need but John Kentish did not have the power under Thomas Kentish’s Will to appoint them on his own.

Fortunately, the charity had a very competent solicitor, John Samuel Story, who owned several properties in the centre of St Albans44. He referred the matter for Counsel’s Opinion via the firm of Alexander and Son of Carey Street near Lincoln’s Inn. The instructing document, with the Opinion of Mr George Harrison written on the same document, is held in Bedfordshire and Luton Archives and provides a fascinating picture of the charity at that time45. The document is dated March 1830.

The instructing solicitor raises a number of issues, including that of Mr Smith being in ‘a confirmed state of mental incapacity and altogether incompetent to the management of his own affairs’. He asks Mr Harrison to advise on how many trustees there should be, noting that, although nine had often been the number, eleven were appointed in 1785. He goes on to mention what he regards as irregularities in the management of the charity, particularly in the application of the funds. He even sets out details of the accounts from 1744 and 1829 respectively, pointing out that there has been backsliding between the former and the latter. He says that trustees have kept money back towards the cost of new farm buildings but, in his view, ‘altho the present buildings may be old, they have been kept in such a state of repair that, even at this time, there is nothing to indicate any immediate want of new buildings’. Moreover, the trustees have allowed themselves more than the £10 provided under Thomas Kentish’s Will to cover their own costs, including journeys to the farm.

Turning to the provision of funds for beneficiaries, the solicitor states that trustees have, on occasion, paid the money directly to the families instead of paying it to the masters or teachers.

Instances have occurred in which a parent has received £12 a year and the Boy has been placed out to a school at 6d or 1s a week – where the Boy has merely attended an Evening School – occasionally, as the parent himself states – and where the Boy has been upwards of 16 years of age and in regular employ as a labourer, at the time the parent has continued to receive the allowance. Also, sometimes there have been 5, 6 or more Boys upon the Charity at once.

All of this sounds very damning but he concludes his instructions by saying, ‘altho there is not any thing to implicate the Trustees in any flagrant dereliction of Duty yet, the irregularities above noticed certainly call for the immediate establishment of a more determinate and better regulated system of administration.’

Mr Harrison’s response, written in a space beside the text, is in much more hurried handwriting. Dealing with the points in a business-like fashion, he gives his Opinion as follows:

- The number of trustees was not completely laid down by the Will ‘but the number 9 seems to have been fixed on’ and he recommends this to be the number.

- The appointment of new trustees cannot be made jointly by the Revd John Kentish and Mr Smith because of ‘the incapacity of the latter.’ Therefore, the Court of Chancery must appoint a trustee who will act with John Kentish to appoint new trustees.

- ‘The application of the Charity funds has not latterly been according to the donor’s Will.’ He agrees with the instructing solicitor about the various irregularities but hopes that these can be remedied without recourse to the Courts.

- Finally, he says that, ‘I think that the Trustees must apply the clear annual income of the Charity after the deduction allowed by the Will, in maintaining, educating and apprenticing 4 objects of the Charity. If there is a deficiency of objects or a surplus income, an application to the Court of Chancery will be necessary.’

We know what the Revd John Kentish thought of this Opinion because a letter is preserved in Bedfordshire Archives from him to Mr Story dated 10 March 183046. In this, he says that he is ‘happy to receive the Opinion, although some of the circumstances disclosed are not of the most pleasing kind.’ However, commenting on the instructing solicitor’s view of the farm buildings, he says that ‘the judgement formed of the state of the farm buildings was mistaken because the house, barns etc are far from being in sound repair.’ (Interestingly, the farmhouse was rebuilt twenty years later.) He goes on to say that he would like Mr Story and his son to be appointed as trustees because ‘difficulties would have been avoided if a person of legal knowledge and experience held office among the trustees.’

After this, the due processes were gone through. An Order confirming Mr Ralph Thrale Smith being ‘of unsound mind’ was made on 13 August 183147 and, on 28 October the same year, a Deed of Appointment of new trustees was signed48. Under this Deed, Mr Henry Alexander was authorised to act on behalf of Mr Smith and he and John Kentish appointed John Samuel Story, Anthony Brown Story, John Newball Bacon, Richard Kentish, Thomas Foreman Gape, Stephen Smith and Thomas Rogers to join them in being trustees.

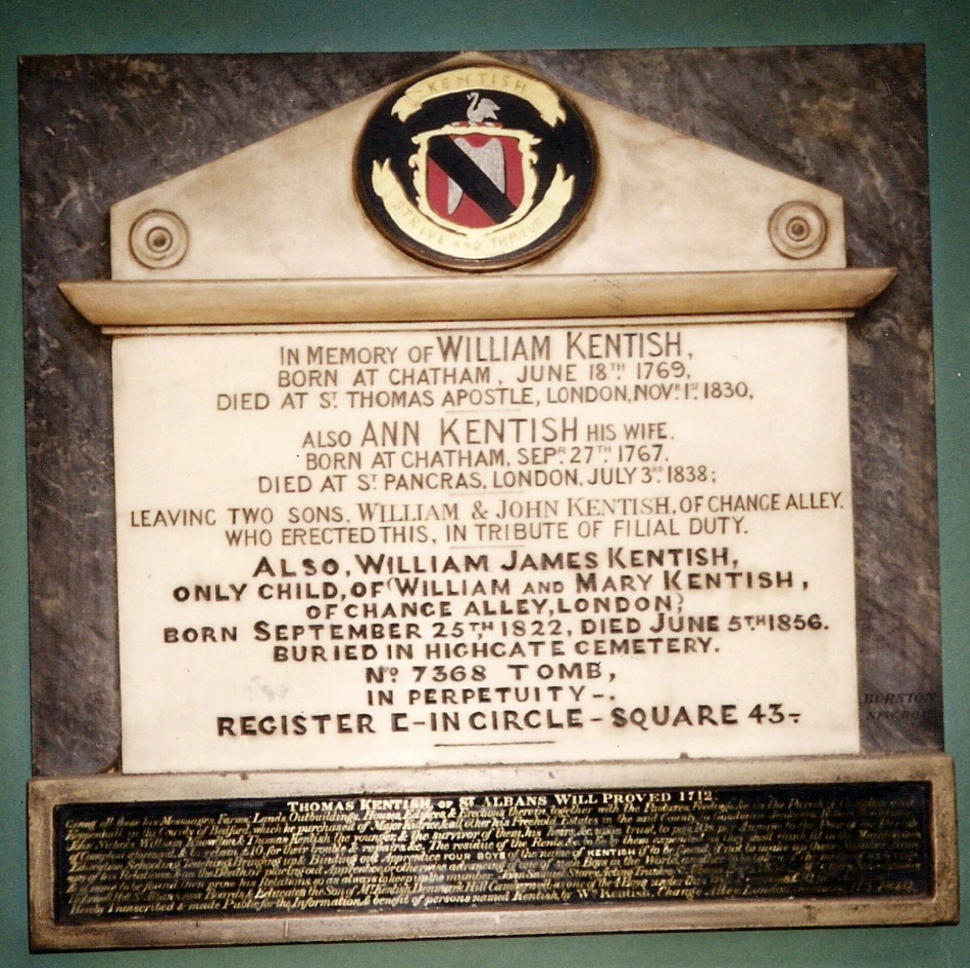

There is a further picture of the charity at this period on a rather curious memorial tablet in the church of St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London. The tablet commemorates William Kentish, his wife Ann and their grandson, William James Kentish of Change Alley, London. At the bottom of the tablet is what can only be described as an advertisement for Thomas Kentish’s charity. After reciting an extract from the Will, it says: ‘John Samuel Storey, Acting Trustee, St Albans, Herts 1832.’ Underneath, there is a postscript which says,

Mr Clare, Schoolmaster, Holywell Hill, St Albans now Boards and Educates the Son of Mr Kentish, Denmark Hill, Camberwell; as one of the 4 Boys under this Will & receives £50 per Annum. Hereby Transcribed and made Public for the Information & benefit of Persons named Kentish, by Wm Kentish, Change Alley, London, January 17th 1840.

3. Increasing regulation

Although, since Elizabeth I’s reign, there had been legislation affecting charitable activities, it was in the nineteenth century that the regulation of charities began in earnest.

In 1849 a special commission was established by royal warrant and recommended the establishment of a permanent Board of Charity Commissioners. A bill introduced in 1851 was unsuccessful, but following a change of government in 1852 a less comprehensive measure was introduced which resulted in the establishment of a permanent Board of Charity Commissioners for England and Wales under the Charitable Trusts Act 1853. This Act was the ancestor of the Charities Acts 1960, 1993, 2006 and 2011.

Under this Act, the commissioners were empowered to inquire into the management of charitable trusts, although some specified charities were excepted (e.g. those of universities, churches, friendly societies, etc.). The Board was enabled to appoint officers of the Charity Commissioners as official trustees of charitable funds, subject to Treasury approval. The Board’s secretary was designated a corporation sole for the purpose of holding charitable lands and given the title of Treasurer of Public Charities (changed in 1855 to Official Trustee of Charity Lands).

The commissioners’ powers were strengthened by the Charitable Trusts Amendment Act 1855 which required charitable trusts to render annual accounts of their endowments. Further strengthening resulted from the Charitable Trusts Act 1860 which enabled the commissioners to exercise certain powers regarding the removal and appointment of trustees, the vesting of property and establishment of schemes for the administration of charitable trusts previously exercisable by the Court of Chancery. The powers of the Charity Commissioners in respect of endowments held solely for educational purposes passed by Order in Council to the Board of Education under the Board of Education Act 1899.

Not surprisingly, Thomas Kentish’s charity was affected by these legal powers. The Charity Commissioners wrote to the trustees on 6 December 1904 to say that, in pursuance of the 1899 Act, they were to separate the part of the endowment ‘held solely for educational purposes’ from that part which was for the poor of Campton.49 A draft Order was enclosed which provided for a sum of £20 in Consols to be ‘placed to a separate account in their books to be entitled Beds. Campton, Thomas Kentish’s Charity for the Poor’ and the dividends were to be remitted to the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of the Parish of Campton. The Order directed that the remainder of the endowment was to be for educational purposes only and the charity was to be called Kentish’s Educational Foundation. This Order was completed on 31 January 1905 and the charity’s new name was established.

Only five years later, on 11 October 1910, the Board of Education made a Scheme for the governance of the Foundation which radically changed its composition. Although the number of trustees remained at nine, only four were to be appointed by the other trustees. The other five were to be appointed by Hertfordshire County Council. Bedfordshire County Council, St Albans City Council, the Senate of the University of London and the Governing Body of the City and Guilds of London Institute respectively. In essence, this remained the composition of the trustee body until 2009, when the trustees, using powers granted by the Charities Acts 1993 and 2006, made all the trustees co-optative apart from the Vicar of St Stephen’s parish, who was to be ex officio. In some ways, this was a return to Thomas Kentish’s own wishes.

The 1910 Scheme, as well as setting out administrative procedures, established ‘Kentish Exhibitions’, which were for boys who were at secondary schools, technical institutions, universities, technical colleges or teacher training colleges. The grants were to be for tuition or entrance fees and/for maintenance costs. Although preference was to be given to boys with the name of Kentish, or who were ‘kin to the Founder, the said Thomas Kentish’, there was scope for awarding grants to other boys.

These conditions persisted until 9 November 1972, when a Scheme made by the Secretary of State for Education and Science introduced girls for the first time, defining ‘beneficiaries’ as ‘boys and girls and young persons who, in the opinion of the Trustees, are in need of financial assistance’ with a preference for boys and young men of the name of Kentish and, secondly, to boys and girls and young persons who are of kin to the Founder, the said Thomas Kentish.’ This Scheme was also less restrictive about the type of assistance that could be given and gave the trustees discretion to determine how they could help the beneficiaries: for example, by paying for tools, equipment, uniform, travel or music lessons.

On 24 August 2009, the Charity Commission made a Scheme which allowed the trustees to concentrate their grant-making activities on the counties of Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, after satisfying their responsibilities towards needy ‘Kentish’ applicants. This formalised arrangements which had been undertaken for some years and which had seemed sensible to the trustees, bearing in mind the limited resources and the strong connections with these two counties.

Part 3: Kentish’s Educational Foundation

1. The charity in times of change

Two hundred years after the death of Thomas Kentish, the charity was in good shape, with its modern name and new constitution established by the Scheme made by the Board of Education in 1910. By then, there were, sadly, no trustees who were members of the Kentish family, although ‘Kentish’ beneficiaries continued to be supported up to the present time. Camptonbury Farm was still being farmed by the Lamb family and the rent had not risen very much since 1712. In 191250, it was £100 per year, compared with £80 in 1712. It was to rise to £144 in 1920. The trustees had a Clerk, Mr Barnes, (soon to be followed by Mr Denis Lawrance), who was paid £10 per year, and two boys with the surname Kentish were being supported in their education51.

Two years later, war broke out and for four years the world struggled with the most extensive and destructive conflict in history. This is not, however, evident, in the Foundation’s account book for that time, where the only references to the Great War are receipts from a War Loan, interest on War Stock and War insurances. This serves as a reminder that, before the advent of air raids, the civilian population in England tried to get on with their lives relatively normally, despite the devastating effects on the young men who served in the armed forces. During those years, the trustees supported several boys in various educational establishments, including Emanuel School in Wandsworth and Clark’s College, a hugely successful college founded by George Clark in 1880 and based at this period in Chancery Lane, London.

After the First World War, the Foundation continued its work in the conscientious way which has characterised it for much of its life. There was usually at least one member of the St Albans Cathedral clergy acting as a trustee and, at a period when hierarchical considerations carried a little more weight than they now do, the Dean of St Albans usually took the Chair. Successive Deans who served as trustees were the Very Reverend George Blenkin, Edward Henderson, Cuthbert Thicknesse, Kenneth Matthews and Noel Kennaby. Other trustees were appointed in accordance with the 1910 Scheme and these were male until Hertfordshire County Council appointed Mrs E Garrett MBE in 1937. The Clerk, Denis Lawrence, died in 1919 and was replaced by Mr W G Marshall. He was replaced in 1922 by Mr Henry J Loe, a solicitor who worked for the firm of Thompson and Debenham’s, who died in office in 1947. The Minutes of the meeting held on 29 March that year recorded the trustees’ sorrow:

The Trustees placed on record their very great sorrow at Mr Loe’s passing. He had taken a personal interest in all the Beneficiaries of the Trust and their parents, and had taken a great deal of trouble to discover any of the Kentish kin who were entitled to consideration for an Award. Mr Loe’s greatest gift was his considerate and reliable friendship, and the Trustees felt that they had lost a great friend and public servant.

Many of the trustees’ meetings had taken place in Mr Loe’s own office at 6 St Peter’s Street, St Albans. Later, meetings took place in various locations, including the old Town Hall, Sandfield Girls’ School (where one of the trustees, Miss Peggy Johnson, was headmistress), Francis Bacon School, the St Albans Diocesan Office in Holywell Hill and, in recent times, in St Stephen’s Church Centre. For over a hundred years, the meetings have generally been held on a Saturday morning. The trustees have also made periodic visits to Camptonbury Farm, with lunch in a nearby pub.

As with the First World War, the work of the Foundation continued without a break during the Second World War. Although a few bombs fell on St Albans – some of them intended for somewhere else – it was generally a safe place to live. Twelve thousand people were evacuated there from London, many of them staying on after the War53. The first reference to the War in the trustees’ Minutes appears on 20 July 1940, when the Clerk reported that a ‘Cultivation of Lands Order had been served on the tenant of Camptonbury Farm [Mrs Lamb], a copy whereof had been forwarded to him, and he was directed to write to the Bedfordshire War Agricultural Executive Committee for information as to the financial help that would be accorded to the farmer.’ Under regulations brought in as part of the war effort in 1939, local authorities surveyed farmland and served notices on tenants to increase cultivation and food production. In 1942, the Bedfordshire War Agricultural Executive Committee reported on Camptonbury Farm:

The land is being worked. A certain acreage of corn has been drilled and manure has been spread. The hedges are being trimmed. From a food production point of view the production is fairly reasonably satisfactory, but, as you probably know, the tenant, Mrs Lamb, is an old lady, somewhere about 70 I should imagine.

Although St Albans was a fairly safe place in which to live during the War, the homes of some of the beneficiaries were not. On 17 April 1941, a tragedy occurred which still makes painful reading today. At the trustees’ meeting held on 17 May 1941, ‘The Dean reported to the Trustees the death of John Spencer and Peter James Kentish, as the result of enemy action. John Spencer Kentish, who was 17, had made up his mind to join the Fleet Air Arm in June, and Peter was at Tiffins Grammar School. Both boys had been a credit to the Trust.’ Photographs of the boys were pasted into the Minute Book. They show John looking sensible and serious and his younger brother smiling engagingly.

The Second World War finally ended in August 1945. However, the Clerk’s Minutes of meetings held in June and December that year make no mention of it at all and concern themselves with grants to beneficiaries, trustee appointments and finance. When Henry Loe died in 1947, the trustees appointed his assistant, Miss C L Sharp, to be the Clerk at a salary of £25 per year. The next year, she reported55 an alarming piece of news about the Foundation’s title deeds:

The Clerk reported that there was still no trace of the two Deed Boxes, held by Barclay’s Bank Ltd in 1919, but which could not now be traced.

These boxes appear to have contained the deeds and papers which were listed in a Minute of a meeting held on 13 September 1919, including title deeds of Camptonbury Farm, Minute books, nineteenth century apprenticeship records and correspondence. It was a great loss, both to the Foundation and to archival collections generally. Access to those papers would have helped to fill in some of the blanks in this history. However, it was not the end of the story. In 1959, the new Clerk, Mrs Stratton, reported that there was an accumulation of old papers in the strong room at Thompson and Debenham’s. She worked for another firm of solicitors, Ottaways, so the papers needed to be moved. The then Chairman, Mr James Baum JP, ‘reported that he collected all the deeds from Mr Debenham’s strong room, a rather large accumulation, some of which dated back 100 years or so… He had contacted the County Archivist of Bedford and deposited the deeds with her… A copy of the Will had been found and proved to be most interesting.56

The documents held at Bedfordshire Archives are clearly those which were deposited by Mr Baum. Although a few are versions or copies of documents listed in 1919, the collection is not the same and we can only speculate about the fate of the two deed boxes. Perhaps, one day, Barclays Bank will find them in some dusty vault.57

2. Boys and young persons

Although the trustees and Clerk have plenty of work to do in managing the investments, being good landlords of Camptonbury Farm and complying with charity legislation, the principal focus of the Foundation is, and has always been, the support of children and young people who are pursuing their education. In that respect, the vision of the charity is the same now as in 1711, when Thomas Kentish wrote his Will.

But over the three hundred years of the Foundation’s existence, the types of education available to children have changed almost beyond recognition. Although there were always some educational opportunities for girls, albeit limited, the main concern of families in the eighteenth, nineteenth and much of the twentieth century was to find trades and professions for their sons, who were to be the breadwinners. Girls were generally expected to be trained up for domestic work, either in service or, more likely, in a family home. In well-off homes, women could be more like managing directors, organising and instructing a large household. However, it was natural that Thomas Kentish should seek to provide for boys in his extended family by financing apprenticeships and the education which led up to them. Until the end of the nineteenth century, this was the main thrust of the trustees’ work.

After the 1910 Scheme of the Board of Education, which set out very specific provisions as to the award of grants, the trustees supported boys who were going to secondary and technical schools. These schools charged fees, although, by the outbreak of the Second World War, nearly half the places in grammar schools were free. Despite the free places, poorer families could not afford to send their sons to grammar school because young teenage boys (and girls) were expected to work and contribute to the family finances. The compulsory school leaving age, which was regulated by statute from 188058 onwards, rose in stages from 10 in 1880 to 14 under the Education Act 1918. The Education Act 1944 changed everything, making secondary education free for all children up to the age of 15 and setting up the 11-plus examination. A Minute from 17 March 1945 records that, ‘the effect of the new regulations under the Education Act were considered by the Trustees and the Clerk was directed in due course to go into the matter and report at the next meeting.’ At the next meeting, held on 9 June 1945, the Trustees…were of the opinion that, in future, maintenance and book grants would be required more than school fees.’

The 1910 Scheme introduced ‘Kentish Exhibitions’, which fell into two categories – Junior and Senior, the former relating to secondary education and the latter to university, technical college or teacher training college education. Junior exhibitions provided school fees and/or maintenance payments (the latter not exceeding £10 per year or £30 for boarders) and senior exhibitions a grant of up to £200, either as a single payment or spread over four years. The trustees adhered to these provisions but, eventually, questioned the size of the grants. A Minute for 29 November 1958 records that, ‘Mr Simkins queried whether it was possible for the Scheme to be revised to bring it up to date with present day values. The Chairman stated that he would make enquiries at the Ministry of Education and report at the next meeting.’ The Chairman (James Baum JP) literally visited the Ministry of Education and received encouragement to consider revisions. The Scheme was eventually substantially revised in 1972 and the trustees were permitted to relax the provisions before then.

For most of the twentieth century boys with the surname Kentish were supported by the Foundation, although there was a sprinkling of other surnames. For example, in 1919, the trustees awarded a junior exhibition to George Wiggs of Watford, who was said to be ‘a direct descendant of the founder’, and his fees for St Albans Grammar School were paid until 1927. He also received a maintenance grant. Sometimes, it was difficult to find enough boys with the surname Kentish or who were descended from the founder’s family and then advertisements were placed in the Herts Advertiser, Bedfordshire Standard and even the national press.

Generally, the beneficiaries were from the local area but it is clear from the names of the schools recorded in the Minutes that the trustees flung their net fairly wide. Fees were paid to, amongst others, St Albans Grammar School (now St Albans School), Clark’s College, Wandsworth Technical School, Eltham College, Wilson’s Grammar School (Camberwell), Sir Walter St John’s Grammar School (Battersea), the Tiffin School (Kingston), Raynes Park School, St Dunstan’s College (Catford) and the Queen Elizabeth School, Wimborne. For the first half of the twentieth century, fees at these schools were up to five pounds per term.

The trustees were also willing to pay for school clothing and the Minutes contain a few lists of clothes, with prices. For instance, the Minutes of 29 February 1936 record that a boy referred to as T A R Kentish, who was at Wilson’s Grammar School, received a vest, a shirt, gloves, a tie, flannels, shoes (two pairs), and a suit at a total cost of three pounds, eleven shillings and ninepence. These clothes were all purchased from Holdron’s department store in Peckham, which was later acquired by the John Lewis Partnership and sold in 1948. This beneficiary was bought quite a lot of clothing, possibly because he was growing rapidly. For instance, he was bought mackintoshes in November 1935 and October 1936 respectively and three pairs of shoes and a pair of boots during the same period.

The school and college reports of all the applicants were scrutinised by the trustees then, just as they are now. Mostly, they found the reports ‘satisfactory’, or ‘extremely satisfactory’. On one occasion, it was reported that a school report (of L T Kentish)59 ‘was considered more satisfactory than the one for the last term’. There was obvious pleasure when a particular boy did well. On 18 November 1944, the Minutes record that the report of Brian Kentish, who attended St Dunstan’s College, ‘was received with great satisfaction, and it was decided that the Dean should write to the boy congratulating him on such a fine result of the term’s work’. Disappointment was in store for them, however. Two years later, Brian’s report was ‘not quite what the Trustees would have wished’60. It is not difficult to imagine the trustees discussing this case and regretting that Brian had not kept up his former high standards.

That the trustees cared personally about their young beneficiaries is clear from the Minute books and this is still very much the case. Sometimes, they felt the need to interview the boys and their parents. In 1945, following a series of unsatisfactory school reports, one boy, Ian Kentish, and his mother were invited (one might say, summoned) to the Deanery in St Albans to meet the Dean and Henry Loe, the Clerk to the Trustees. Henry Loe’s note of the meeting shows something of the patrician attitudes which still prevailed then, but is also kindly. He records that, ‘Ian is a big overgrown boy for 15. He admitted his reports were not satisfactory. He apparently would like to go on the land farming. The Dean pointed out to him the advantages of obtaining a School Certificate before any arrangements could be made for him to enter agricultural college. I formed the opinion that the boy had outgrown his strength, that his feet had caused him trouble (Mrs Kentish afterwards told me he had been attending a specialist with regard to them) and had stopped him from playing games. He thought his Masters did not like him and therefore did not try. He had drifted to be with the lazy boys of the School [Wimborne School] and had not improved by so doing. He appears a nice lad if one could get over his reserve which is very difficult.’61The trustees continued to support Ian after he transferred to Bournemouth College, but he subsequently failed his Matriculation Examination and joined the Army. What the trustees felt about this is not recorded, but it is likely that they accepted it with mixed feelings. Trustees of grant-making charities like the Foundation find that they need to balance their natural interest in their beneficiaries’ achievements and wellbeing with the limitations of their role.

3. The Foundation expands and thrives

Throughout the 1960s, the trustees were chafing at the bit to have some of the prescriptive provisions of the 1910 Scheme changed, but it was not until 9 November 1972 that the Secretary of State for Education and Science made a new Scheme. This left much of the 1910 Scheme intact but radically altered the way in which the grants were to be awarded. Instead of setting out the precise sums to be paid to beneficiaries, this enabled the trustees to make their own rules as to the value and conditions of the grants, which were to be for a number of purposes, including study at schools, colleges and universities, educational travel, music lessons or for tools and equipment. More significantly, it brought in girls for the first time, defining the beneficiaries as ‘boys and girls and young persons who, in the opinion of the Trustees, are in need of financial assistance and, subject as in sub-clause (3) below provided, a preference shall be given – First, to boys and young men of the name of Kentish; and Secondly, to boys and girls and young persons who are of kin to the Founder, the said Thomas Kentish.’62

Within a year, grants were being made to girls as well as to boys and, in recent years, girls and young women have generally outnumbered males as beneficiaries. But the widening of the statutory provisions did not itself increase the amount of money available for grants. This was still the rent from Camptonbury Farm plus income from some invested funds. In addition, the trustees needed to take out a mortgage to pay for some new farm buildings. Consequently, grants continued to be made only to young people in the priority category and not to other young people. Sometimes, there was difficulty, as in past years, in finding enough of these. A Minute of 19 May 1984 records that, ‘it was noted that the present number of grantees was six and that after the Summer term, 1984, there would be a possible reduction of three who would be terminating their particular studies. In view of this it was AGREED that the availability of grants from the Foundation should be advertised locally in the Herts Advertiser and the Bedfordshire Times.’

In the 1990s, an opportunity arose to increase the amount of income significantly. By then, the old farm buildings, including two large barns and some Victorian brick buildings, had become redundant and were being used for storage. The trustees, under the Chairmanship of Professor Alan Deyermond, began to see them as being suitable for conversion into houses and sold, although it was recognised that this might not appeal to the Foundation’s tenant. However, the new young tenant, married with a growing family, was interested in exploring whether he might purchase and extend the farmhouse. The prospect of a ‘deal’ was opened up. Discussions began, professional advisers were brought in, outline planning permission was sought and eventually, in 1998, the proposals came to fruition. The Foundation sold the house (with a newly-restored roof) and a paddock to the tenant, and the old farm buildings, with outline planning permission for four houses, to a developer. Although there were some regrets over the alienation of the house and old buildings, the trustees found themselves with almost four times as much income to expend on grants. It was no wonder that they and the Clerk decided to meet for a celebration lunch at the Black Lion pub in St Albans. At the next meeting,63 they agreed that the lunch held on 17 October 1998 ‘had been a very happy occasion.’

With income flowing from the invested sale proceeds, the trustees soon decided to award grants to young people who were not ‘Kentish’ applicants, as well as to those who were. But how were these young people to be selected? Although, in theory, applicants could come from anywhere in the country, the amount of income available was insufficient to support large numbers of boys and girls. The answer was clear. As Thomas Kentish had been active in both Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, these two counties were the appropriate focus of the trustees’ grant-making efforts. Since 1999, around twenty-five grants have been awarded each year, at least three-quarters of them to young people resident in the two counties. In 2009, the Charity Commission formalised these provisions. These days, there is no need to place advertisements in newspapers, asking for applications, because there are several directories and databases, many of them on the internet, which list grant-making charities.

Grants are awarded for one year at a time but eligible applicants have always been able to re-apply. Consequently, the trustees have come to know some families – particularly the ‘Kentish’ ones – over a period of many years. The purposes for which the grants are awarded provide a snapshot of the educational system at any given time. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the emphasis was on apprenticeships for trades and professions. From the late nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth century, grants were awarded to boys at school and college who were hoping for careers in the civil service, teaching, farming or management. Since the 1960s, the variety of subjects at school and in further and higher education has widened considerably and all courses are open to young people of both sexes equally, even though the take-up is rarely in equal proportions.

The trustees and their Clerk need to keep their knowledge of educational matters up to date in order to understand and assess the applications which come before them. They study the applicants’ school reports, examination results, university grades and tutors’ assessments. They have seen, with a sense of pride, young people go on to become doctors, nurses, teachers, architects, veterinary surgeons, electricians, hairdressers, musicians, accountants and librarians. But, sometimes, a more urgent request comes in. On a few occasions, the trustees have awarded grants for the purchase of school clothes, just as they did in the 1930s, when young T A R Kentish was kitted out for Wilson’s Grammar School. On one of these occasions, a teacher at a local school referred a family to the Foundation. The father had lost his job, the mother was doing low-paid part-time work and the teenage daughter had grown out of her school uniform. A grant was quickly provided and the daughter was able to attend school in a new, well-fitting uniform.

In all the discussions which take place around the table at trustee meetings, Thomas Kentish’s name is hardly ever absent. It is still his farm at Campton which provides part of the Foundation’s endowment and income. The meeting room at St Stephen’s Church Centre is called the Kentish Room. And it is still his charitable instincts and vision which inspire the trustees, Clerk and beneficiaries. He worked hard as a yeoman farmer and did well. But he knew that, just as in farming, sowing the seeds of education would also produce a harvest. When he wrote his Will in 1711, he was planting those seeds and the harvest has been gathered in every year since then. The work has been done, for the most part, quietly and unostentatiously. And yet, as an example of continuity and public service, the story of Kentish’s Educational Foundation is remarkable.

Appendix: Trustees and Clerks

Thomas Kentish knew that the vitality and longevity of the charity which he founded would depend on the qualities of the trustees who were placed in charge of it. He chose the first ones himself and ensured continuity by providing in his Will for the succession. The Will states that, ‘new trustees are always to be named and appointed by the surviving trustees’.

The first trustees were drawn from his immediate circle and were all trusted members of his family, including a nephew and cousins. Some of these served for a number of years. Godman Jenkyns, for example, who was the son of Thomas’s sister, Rose, did not die until 1746, when he was ninety. There were no retirement provisions for the trustees at that time.

For the first hundred years or so, members of the Kentish family continued to dominate the trustee body but gradually the composition changed. We have seen that, in 1830, John Kentish and Ralph Thrale Smith were the only trustees and the latter was not capable of acting. When new trustees were appointed, one of them was a Kentish trustee. The others were local men who were probably noted for their integrity and probity. This was certainly true of John Samuel Story, who had already served the trustees well as their legal adviser.

The 1910 Scheme of the Board of Education introduced terms of appointment for all the trustees and established the principle of having five representative trustees and four co-optative trustees, an arrangement which lasted until 2009. The appointing bodies, with the exception of the City and Guilds of London Institute and the Senate of the University of London (which was, at that time, the nearest university to St Albans), tended to appoint long-serving members of local authorities and magistrates. Notable amongst these were Mr James Baum JP, who represented Hertfordshire County Council for 22 years. The co-optative trustees were often cathedral clergy, head teachers at local schools or farmers. For example, in the early 1920s, both the Dean of St Albans and Canon George Glossop were trustees. Canon Glossop, who lost two sons in the First World War, was an eminent clergyman who is commemorated in various places around St Albans. Distinguished local head teachers included Mr Ralph Sexton, headmaster of Francis Bacon School, Miss Winifred (Peggy) Johnson, headmistress of Sandfield Girls’ School and Mr Frank Kilvington, formerly headmaster of St Albans School. Farmers have included Mr John Swan, Mr Charles Dickinson and Mr William Dickinson (owner of Cross Farm). The University usually appointed academics, such as Dr A N Boycott, who served as a trustee for 31 years, Dr Elsie Toms JP and Professor Alan Deyermond. The City and Guilds similarly sent some fine representatives, including Mr R E Burnett, who served for 18 years, and Mr Basil Henson. Unsatisfactory trustees (and there have not been many) have usually been the authors of their own fate, because the Foundation’s governing document provides for the removal of a trustee if he or she is absent from meetings without cause for a year.

The Foundation has also benefited from its dedicated Clerks, although it is unclear when the first Clerk to the Trustees was appointed. In the early years of the charity, the trustees used agents to assist them, particularly in relation to the management of Camptonbury Farm, and there is extensive evidence in the records of other professional advisers, such as surveyors, solicitors and accountants. The accounts for the 1880s record payments of £10 per year for ‘management’. In 1908, this has changed to ‘Clerk’s salary’ and, after this, the Clerk is frequently referred to, although the list of names at the top of each set of Minutes does not include the Clerk’s name until 1980, when Mr John Bulmer took over the Clerkship. After Mr Henry Loe’s death in 1947 and until 1980, the Clerks tended to be employees at the offices of the Foundation’s solicitors or accountants. Despite the commitment of some excellent Clerks, this arrangement did not always work well and there was a difficult period before John Bulmer became the Clerk and put the Foundation’s papers in good order. Eight years later, he retired and Mrs Margery Roberts was appointed as the new Clerk to the Trustees.

Trustees in 1712

- Godman Jenkyns Esq

- Robert Jenkyns Gent

- John Nichols of Idlestrey (ie Elstree)

- William Knowlton

- Thomas Kentish the Younger of Tenements

No Clerk

Trustees in 2012

- Mr Basil Henson (Chairman)

- Mrs Hilary Burningham

- Mr William Dickinson

- Mr Michael Highstead

- Mr David Nice

- The Revd David Ridgeway

- Dr Joan Ripley

- Mrs Alison Steer

- Mr Robin Younger

Clerk to the Trustees: Mrs Margery Roberts

Note on Sources

The chronicler of a charity’s history is not entitled to make anything up and state it as fact, although there has to be a coherent and continuous text in order to make the work acceptable to the interested reader. In the case of Kentish’s Educational Foundation, and Thomas Kentish himself, the records are patchy, and this is made clear in the book. Where possible, all the documents which have been consulted are identified, either in the body of the text or in footnotes, and where there is speculation, or an educated guess, this is also made apparent. The records improve in quantity the nearer one comes to the present day, but then the question of data protection becomes an issue. It would not be appropriate for a work like this to reveal personal details about present or recent beneficiaries.

A copy of Thomas Kentish’s Will, which tells us so much about him and his bequests, is held in the Public Record Office. A copy of his mother’s (ie Rose Woolley’s) Will is also kept there. There are surprisingly good records of land transactions and other legal documents relating to Thomas Kentish and his family, dating from the seventeenth century, in the Hertfordshire Archives office in Hertford. Similarly, there are excellent records in the Bedfordshire and Luton Archives, located in Bedford, particularly those which were deposited by the trustees in 1959 and which are kept together under the heading of ‘Kentish’s Educational Foundation’. The staff in both offices have proved to be most helpful.

The Foundation still holds its own Minute and account books covering much of the twentieth century and these have been studied thoroughly with a mixture of fascination and nostalgia. Various extracts and quotations have been included in this book.

Mention should be made of the admirable work of archivists and others in compiling internet databases such as ‘Access to Archives’, which have made research so much more efficient than in the past. But, ideally, these should be viewed as an invitation to research, rather than the research itself. Nothing can replace the wonder and satisfaction of handling and reading a beautifully-handwritten parchment document dating from the middle of the seventeenth century. In the case of Thomas Kentish, we are able to read conveyances which he signed, see the land which he farmed, and stand beside the place where he lies buried. In doing so, we feel very close to the man who founded a charity which is still thriving after three hundred years.

Text copyright Margery Roberts 2012